6. March 2024

To work with the process

Christine Chapman and Marco Blaauw in conversation with Kamila Metwaly, artistic director of MaerzMusik:

Marco Blaauw: Kamila, how did you get on the traces of Lucia Dlugoszewski? How did you discover her?

Kamila Metwaly: It’s an interesting anecdote because I came across her work through the work of Pauline Oliveros. The opening quote of the book of Oliveros, “Deep Listening,” is a quote by Dlugoszewski:

“The first concern of all music in one way or another is to shatter the indifference of hearing, the callousness of sensibility, to create that moment of solution we call poetry, our rigidity dissolved when we occur reborn – in a sense hearing for the first time.”

— Lucia Dlugoszewski

It was, for me, an unknown name. I didn’t know her. I read the book, and I completely forgot this quote for years. Then, one day I was sitting and I was thinking: “Who is she? I have no clue who that person is.” It was that particular quote that really had to do a lot with listening in connection with Oliveros in which she explores the distinction between the mere physical act of hearing through the body, through the ears, and rather an instant or a situated listening that is influenced by very different elements. And then I started delving into the work of Dlugoszewski and tried to find the source of the quote that I found absolutely fascinating.

Christine Chapman: What was the first music that you heard?

KM: Space is a Diamond, actually. Which was mind-blowing, to be honest. It was very interesting, and in the beginning, I was almost repelled by researching her works. That was before Amy Beal’s work, Terrible Freedom, came out, and it was very hard to find more information about her. So I started digging and digging further, getting stories here and there, and a few interesting articles from the New York Times popped in. So it sounded like she was very present, but no one was able to really understand the music. Because if you have a few works put out there by a composer, you can’t really construct a full story of the musical language and the relevance of their work. So yes, it’s great that Wikipedia writes that she invented instruments… So what? It doesn’t mean anything until you actually understand what the purpose of these instruments is for her and her work.

MB: So, how did the festival MaerzMusik then come to Ensemble Musikfabrik?

KM: It was your work with Harry Partch. We thought about it for a long time, who we could invite who can also engange in a research process. Who can take on a project that is not about mere reconstruction or presentation of a concert format but to carry a whole re- search into the philosophy of the work of the composer. Because that is what we were looking for. We were trying to find an interesting collaborator and a partner who could actually delve into those questions and carry this project beyond the mere presentation of a festival. So your work in general, and the openness to- wards experimenting with sound, form, and music, was at the forefront of the invitation. But mainly, the sensitivity of how you work with those very fragile stories or material and contour was the key to inviting you. And that’s why we knocked on your door, and we’re very happy you accepted our invitation.

MB: Your invitation, of course, fell on fertile ground because some of us had already encountered Dlugoszewski on individual research paths, and then, suddenly, there is this fantastic gift on the table.

CC: I find it fascinating that you and the festival asked us as musicians to do the research, to literally go to the Libarary of Congress in Washington D.C., and spend a week digging in the scores, notes, and sketches. That’s been a fantastic experience for me as a performer.

KM: It’s really great to hear.

MB: I’m also fascinated by the path to the concert. Usually, a new project starts with rehearsals, then we play the concert. In this case, the project begins with research. It slowly takes shape, which is exciting because the production process is so different. We discovered lots of things in the Library of Congress. You are about to travel to the Library of Congress, so what are you expecting to find? What will your focus be when you walk in there?

KM: I’m not really sure, to be honest. The question is, what are the stories that complete all of these works and connect them to one another? We cannot define Dlugoszewski in these two concerts we will present. It’s just the tip of the iceberg of her work and who she was. I think it’s very sensitive work to re-introduce composers into the repertoire of contemporary music or music at large without falling into project thinking, such as “That’s a project, and then we do another project” – especially with those composers that are not well known. Or then become the new mavericks of contemporary music.

It requires sensitivity. How do we reintroduce them because they’ve always existed, and how do we present the bigger arc of who they were? Because all of these stories, all the biographical notes of her movements, her relationship to Erick Hawkins, the choreography, her own physicality while performing, and the timbre piano on stage, all these aspects are essential, in my opinion, to introduce the music that really taps into the philosophical quest of Dlugoszewski in particular. Maybe this is what I would like to try to find: bits and pieces we can use to construct her portrait in Berlin.

As you told me, it’s a huge library, and we only had a year and a half, which is very little time to think about someone with a repertoire and work since the 1950s. And the works also change. They’re not static – some- times they are, but often they also grow. They are deconstructed; they become something else.

MB: It’s a little bit like rewriting history: We have the actual results of her life in boxes, and we can dive into them. There are lots of anecdotes… I knew some about “Space is a Diamond”, and when I opened the “Space is a Diamond”-Box I found completely different materials that contradicted the story I had often heard. The piece was actually widely planned and sketched, then carefully composed, and even budgeted. We found a little budget sheet with fees for the dancers, fees for the choreography, fees for the costumes, fees for the trumpet player. That is amazing, and the sketches she made are amazing. I think they are beautiful enough to put in a frame.

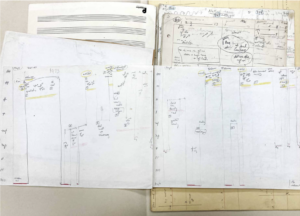

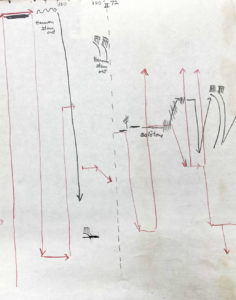

CC: That will be an interesting thing for you, Kamila, I think. There’s an incredible amount of material from when she was in her production period. When she was writing, composing – she had this whole process of sketching out movement, ideas, and sounds, referred to as maps. They’re large sheets. It looks pretty chaotic, definitely chaotic, and perhaps random. Still, after you look at them for a while, you do notice a real sense of rhythm in the movements on the page. You see, how much a part of her creative process was the imagery of living in the dance company with Erick Hawkins, seeing the bodies moving and having that being part of her creative process. I think this can be seen in some of these maps. If I could wish something from you when you go back to the Library of Congress, it would be to photograph or scan some of the maps you find that are exemplary of some of these ideas.

KM: That sounds beautiful!

MB: Some of these maps even start with loose words, then words become sentence, and then there’s a little story, and then there is movement to it.

CC: You will also learn more about some of the titles of the pieces, which seem like a random collection of words, but they’re actually not.

KM: That’s definitely something I’m curious about: The origin of the titles. Because it doesn’t sound random at all, right? Also, the fact that some of the works have two titles, one for dance and one for music. I guess, that she also wanted to have her own established path as a composer. Many of these works where presented both with dance and in concert formats without dance. That is very important, she hasn‘t just been a shadow of Hawkins. And that is absolutely fascinating. It’s an essential part of her work. A facet or reality that is very much embedded in many philosophical questions that run through her music, her writing, her titles and what you read in every biography when she talks about „suchness“, for example. It’s fascinating to think about her relationship with sound as a source and material and what it means for her.

MB: One Question about the festival: It’s fantastic that you are presenting the works of Dlugoszewski. Is it for you more the process of creating, or is it the process recreating? Can you say something about that?

KM:

K: I think it’s both. I think it’s also very unique to you as Ensemble Musikfabrik. And I think that this is one of the most exciting parts of the project. It will be unique to your appearances: Your approaches, your reading, performance – presence on stage together with dance. There was, of course, a lot of thinking that we went through, which was about both: on the one hand we present her works in a context of paying a homage to her work in the most honest possible way. And hear the work as something that is static to some extent, bound to a score, or bound to an interpretation of a recording. Our other approach was about extending all these curiosities of Dlugoszewski to maybe new instances and nuances, and to think about how can you transcend that knowledge to – let’s say – the future – a sort of speculation into the archive. For example, when we invited Edivaldo Ernesto, that MaerzMusik was intro- duced to by you, to create a new choreography, we felt that this work is not only a new creation, but is also a curious look into transcendence of the Hawkins/Dlugoszewski technique, aesthetic, form and novelty.

Similarly, this will also happen with the music, either with some of her works that are a bit more abstract or with the commissions. We thought it would also be an interesting moment to invite composers who don’t know anything about Dlugoszewski to find one element in her music, her work, her sound spectrum, and her philosophy that would be interesting for them to explore. That’s really nice because there is this moment when there is nothing final. Do you know what I mean? We’re not presenting excellence; we’re not presenting a mere product that can be moved. Every time the ensemble performs these pieces, I’m sure you’ll come up with something new. Maybe the performance of Space is a Diamond will be different next time; it will go to another space. We allowed ourselves to work with the process.

CC: Speaking of process, I’m very curios to hear how the dancing auditions went with Katherine Duke just a couple weeks ago. Can you give us a summary?

KM: It was very beautiful because it was, on the one hand, an audition, but on the other, sort of a workshop. Katherine really went through Erick Hawkins’ core concepts of movement in relation to the body. This is unique for MaerzMusik because we usually don’t produce; we don’t have those capacities. I think it’s very important that we’re doing this project together because it also influences how we work as MaerzMusik. We become a different kind of host. The audition workshop was very open, kind of a session on the relationship between the composer and the choreographer.

A lot of the dancers said that it reminded them of their classical training. Which makes sense: we are dealing with a classic and classical aesthetic to some extent. So, they were curious about how to bridge their practice as dancers trained in more experimental dance techniques in relation to this classical approach specifictoHawkins.

Katherine Duke will reconstruct as much as possible in the choreographies she is leading because when you pay homage to the original work, it’s important to focus on Erick Hawkins, if you ask me. And then we have the new work by Edivaldo Ernesto with the choreographies he creates.

On the other hand, I feel it’s a very good decision to have these two concerts: one that focuses on just music that allows the listeners to delve into Dlugoszewski’s repertoire without visual distraction, and then presenting works with dance and showcasing her capacity and collaborations in that domain.

MB: Dlugoszewski worked most of her career in the shade of Erick Hawkins so we are deliberate in presenting her works on their own in the full light of the concert stage.